Integrating a Servant Leadership Framework: Preparing Teaching and School Counseling Students for Collaboration

Primary/Corresponding Author: Pamela N. Harris

The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Department of Counseling and Educational Development

PO Box 26170, Greensboro, NC 27402-6170

757-880-5124

pnharris@uncg.edu

Co-Author: Marquita S. Hockaday

Pfeiffer University

Division of Education

Abstract

Culturally responsive servant leadership may serve as a model for school counselor and teacher graduate students to create collaborative partnerships in the K-12 setting. Currently, research about servant leadership in school counselor and teacher preparation programs is limited, and research regarding teacher-school counselor partnerships. Thus, the authors propose an interdisciplinary project in which graduate students in school counseling and teacher preparation programs work collaboratively to create culturally responsive professional development integrating the components of the servant leadership framework. The authors expect the outcome of the project to impact graduate students’ continued professional endeavors, and inform future quantitative and qualitative studies regarding teacher-school counselor collaborative partnerships.

Keywords: collaboration, school counselor education, servant leadership, teacher education

Students for Collaboration

Student success thrives when there are productive collaborations between school personnel (Henfield & McGee, 2012; Shoffner & Wachter Morris, 2010). In fact, The National Science Foundation (NSF, 2011) and The National Institutes of Health (NIH, 2006) have discussed the impact interdisciplinary scholarship could have on solving global issues. For instance, the NSF (2011) has suggested that creating and including more interdisciplinary curricula may lead to large scale societal transformations. On a micro-level, those who advocate for interdisciplinary methods in the K-12 setting report an increase in student engagement, and advancements in students’ critical-thinking skills, and an enhancement in faculty members’ morale (Jones, 2010; Martinello & Cook, 1992). Interdisciplinary collaboration permits educators to model the linkages between content areas while providing students with soft skills, or hidden curriculum, such as leadership and collaboration (Jacobs, 1989; Jones, 2010). Thus, forging interdisciplinary collaboration in the K-12 setting encourages educators to support numerous facets of student learning (Marlow, Bloss, & Bloss, 2000; Shoffner & Wachter Morris, 2010).

Though the benefits of interdisciplinary collaboration are numerous, these partnerships also hold a few challenges. The time and resources needed to create and integrate partnerships can take away from other instruction, and some disciplines or content areas may receive more attention than others (Combs & White, 2000; Marlow, Bloss, & Bloss, 2000). Confusion can occur if all parties involved are not communicating in a timely and open manner (Combs & White, 2000). The pressures of the school day, and unclear definitions of partners’ daily roles and responsibilities contributes to issues with collaboration (Marlow, Bloss, & Bloss, 2000; Shoffner & Wachter Morris, 2010) For example, Combs and White (2000) allude to directions that may not be clear, unresponsive team members, and team members who may not make it to mandatory in-person meetings. The time needed for project completion, limited resources, and lack of professional training in interdisciplinary partnering can also be a hindrance when collaborating on a project across disciplines (Marlow, Bloss, & Bloss, 2000).

Considering the abundance of literature available concerning interdisciplinary partnerships, research examining collaboration between teachers and school counselors has been limited. Marlow, Bloss, and Bloss (2000) conducted a study in which they assessed the benefits and challenges of teacher and school counselor collaboration in elementary and middle school settings. The purpose of the study was to see how teachers and school counselors viewed “the collaborative teaching of social and emotional competency (SEC) skills in grades 1-8 and the perceived barriers and aids to such collaboration” (Marlow, Boss, & Boss, 2000, p. 669). The researchers found differences regarding teacher and school counselor collaboration based on school level (e.g., more elementary educators than middle school educators reported SEC collaborative teaching). Further, several barriers to collaboration were noted, such as inadequate time for implementing projects and lack of administrative support (Marlow, Boss, & Boss, 2000).

In a different approach, Henfield and McGee (2012) discussed collaborative culturally responsive frameworks school counselors and teachers could integrate to promote academic success for Black male students. The researchers provided a vignette, showing how teachers and school counselors could work together, using Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST) and Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT), to meet the personal and social needs of Black male students (Henfield & McGree, 2012). Henfield and McGee (2012) concluded that while literature has recognized the positive impact collaborative partnerships between educators may have on students, there has not been a clear framework created for teachers and school counselors to conduct these partnerships. Thus, Henfield and McGee (2012) suggested infusing the PVEST and SCCT frameworks to impact Black male students’ academic success. Considering school counselors and teachers work toward similar goals, such as assisting students’ with academic success and personal growth (Shoffner & Wachter Morris, 2010; Stringer, Reynolds, & Simpson, 2003), these educators should work together to provide students with the resources to excel. Providing teacher and school counselor trainees with the skills needed to collaborate through practical experience may encourage interdisciplinary practices between these educators (Shoffner & Wachter Morris, 2010).

Current Collaboration Models in Education Programs

Interdisciplinary models in teacher education programs has been thoroughly examined in previous literature (Combs & White, 2000; Millman, 2010; Reidel & Draper, 2013; vanZee, Jansen, Winograd, Crowl, & Devitt, 2013). Accountability and standards based instruction require preservice educators to be equipped with the skills to model how various content areas connect (Reidel & Draper, 2013). Accordingly, Reidel and Draper (2013) created an interdisciplinary model for future social studies teachers at a university’s middle grade teacher education program that integrates global awareness and critical literacy skills. Students engaged in literacy activities (e.g., Think/Write, Pair, Share, read aloud, group discussions) regarding Indian culture (Reidel & Draper, 2013). Reidel and Draper (2013) found that providing students with opportunities to experience Indian culture through hands-on activities, such as showing slideshows of Indian classrooms and movies resonated with the preservice educators (Reidel and Draper, 2013). Additionally, modeling interdisciplinary strategies and showing what these strategies would look like in the students’ classrooms seemed to connect with the students (Reidel & Draper, 2013).

Similarly, Combs and White (2000), created and integrated an interdisciplinary unit project into their secondary methods courses. The instructors motivated undergraduate English, foreign language, and social studies preservice educators to collaborate and create interdisciplinary units (Combs & White, 2000). The preservice teachers worked in teams to choose a topic and create a unit based on the instructors’ clearly defined tasks (Comb & White, 2000). According to Combs and White (2000), including this interdisciplinary model encouraged students to use interdisciplinary approaches in future lesson plans. The interdisciplinary project showed the students’ abilities to work in collaborative teams (Combs & White, 2000). Further, the students shared, “in job interviews principals ask about knowledge and experience with interdisciplinary units and are quite impressed with these products” (Combs & White, 2000,p. 286). The role and expertise of the instructors also seemed to have a positive impact on the preservice educators (Combs & White, 2000).

As a way to prepare preservice teachers to work with diverse learners, Marbley, Bonner, McKisick, Henfield, and Watts (2007) outline a training model that enabled the teaching students to attend growth groups facilitated by supervised counseling interns to promote multicultural awareness. Whereas this model is an excellent way to prepare preservice teachers to address the unique needs of diverse learners, it does not emphasize ways to prepare the counseling interns to do the same. Shoffner and Wachter Morris (2010) discussed the creation of a collaborative class session between preservice English teachers and school counseling interns. In this class, the school counseling interns conducted in-service training to describe the school counselor’s role in meeting students’ needs, and both groups engaged in discussion about concerns and possible solutions that teachers and school counselors may face in working with students. Though this collaboration model occurred during one 75-minute class, the implications resulted in the preservice teachers having a better understanding of the school counselor’s role, as showed through their reflections. Yet, while researchers have addressed the importance of teachers and school counselors collaborating to address the needs of students with disabilities (Webb, Webb & Fults-McMurtery, 2011), and to enhance the learning environment (Fazio-Griffith & Curry, 2008), literature examining collaboration models between preservice school counselors and teachers is limited. Research acknowledging the role of preservice leadership for educators, such as teachers and school counselors, emphasizes the impact of infusing a servant leadership framework to address diverse needs (Bond, 2011; Leeper, Tonneson, & Williams, 2010). Hence, the authors propose a model in which to design a collaboration project between teaching and school counseling students.

Servant Leadership Framework

Educators join and remain in the education field largely due to the satisfaction that is received from helping a younger generation (Nieto, 2003; Sink, 2002). Teachers report satisfaction from not just imparting knowledge, but in also assisting students reach awareness of their own strengths (Carrol, 2017; Noddings, 2005). Thus, servant leadership can serve as a foundation to go beyond the traditional hierarchal approach to teaching (Noland & Richards, 2015), and instead focus on empowering students to reach their full potential. Servant leadership encourages the leader (in this case, the educator) to serve by placing the followers’ needs (in this case, the students) before the leaders (Tate, 2003). Researchers have found seven constructs that form servant leadership behaviors (Panaccio, Henderson, Liden, Wayne, & Cao, 2014), which include emotional healing, creating value for the community, conceptual skills, empowering, helping subordinates grow and succeed, putting subordinates first, and behaving ethically.

Though a growing concept in the education field, servant leadership has previously been reviewed in literature involving teaching practices and teacher preparation. Fitzgerald (2015) encouraged teachers to adopt Spears’ (2010) ten characteristics to better support students and assist them in building resilience; these characteristics include common servant leadership traits such as empathy, healing, conceptualization, and building commitment. Additionally, Noland and Richards (2015) examined how a teaching approach integrated with servant leadership impacted student learning, engagement, and motivation and found that servant leadership positively relates to student engagement and indicators of learning. According to Crippen (2010), once an individual becomes a teacher, he or she is a leader in the classroom, and eventually in the school. Thus, teacher candidates should learn moral and ethical ways to lead, such as the components of servant leadership, in preparation programs before entering the field (Bond, 2011; Crippen, 2010).

More often than not, teacher preparation programs emphasize pedagogy and content knowledge (Leeper et al., 2010), limiting teacher candidates’ exposure to leadership skills (Crippen, 2010; York-Barr & Duke, 2004). Few empirical studies regarding teacher preparation programs, and more specifically teacher preparation program stressing teacher leadership, exists (York-Barr & Duke, 2004). In response to the lack of research, Leeper et al., (2010) conducted a qualitative study with preservice elementary educators to discover these students’ perceptions of teacher leadership and how this concept was integrated into graduate coursework. The findings of the study suggested that teacher leaders build relationships, are flexible, possess good listening and communication skills, and allow students’ needs to inform their teaching style (Leeper et. al., 2010). Further, it was concluded graduate coursework did not align with the qualities of an effective teacher leader (Leeper et al., 2010). Finally, servant leadership has even been used to train undergraduate helping professionals. Fields, Thompson, and Hawkins (2015) conducted a study in which interns read and discussed materials on servant leadership, and then applied these constructs through weekly self-reflection exercises on their internship experiences. Findings showed an increase in the interns’ abilities to empower and serve others. Hence, the potential for integrating the servant leadership framework into a collaboration project between teaching and school counseling graduate students is promising in that this approach may emphasize strengths in both colleagues and future students.

Servant Teaching Collaboration Project

The authors designed a collaboration project between graduate school counseling and teaching students at their respective educational institutions. This collaboration project was grounded in Noland and Richards’ (2015) concept of servant teaching, or that the education process is “relational, empowering, and liberating” (p. 17, as indicated by Hays, 2008) as opposed to hierarchical and authoritarian. Thus, the purpose of this project is twofold: (a.) to integrate servant teaching as a way to promote empowering underrepresented populations in current or future school placements, and (b.) to provide an applicable experience of school counselor-teacher collaboration. The major goals for this project is to identify an underrepresented student population (either in the school counseling and teaching graduate students’ practicum, internship, and/or sites of employment), and then to create a professional development PowerPoint as if the school counselors and teachers had to provide training on working with this identified population to the faculty or staff at their schools. If the teaching and school counseling graduate students are from the same or neighboring campuses, this professional development can be facilitated in front of their classmates; however, if distance prohibits this, the final Power points may be submitted to the students’ respective instructors.

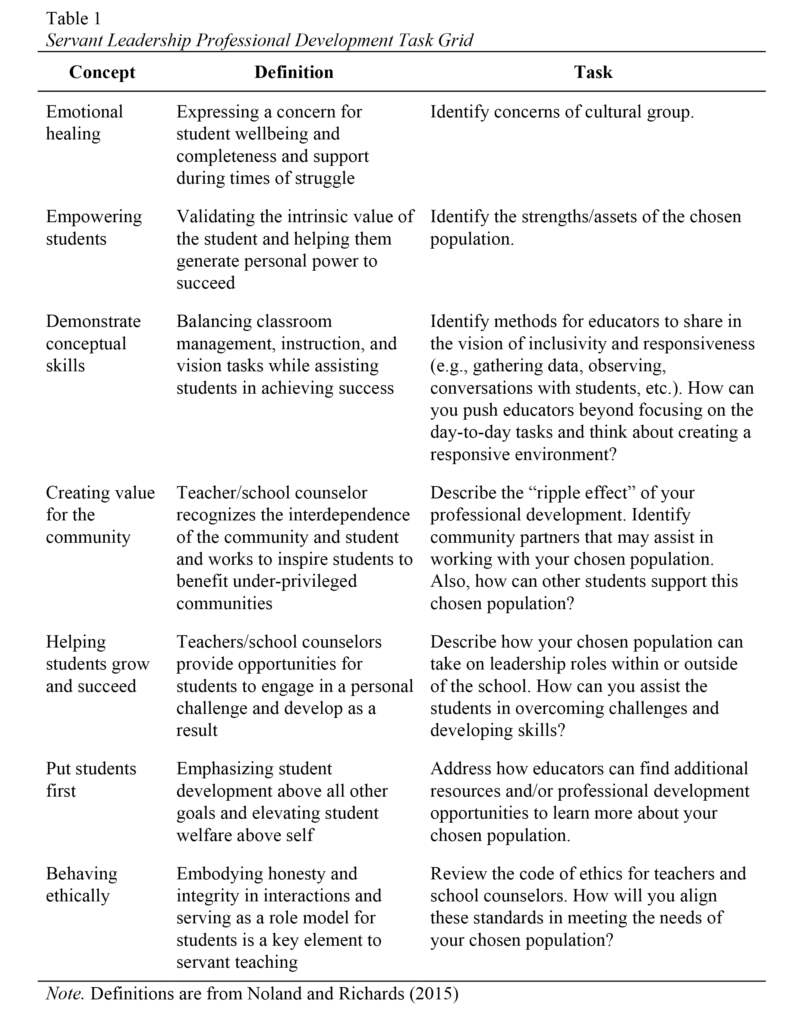

To emphasize servant teaching, the project includes tasks that align with the key dimensions of servant teaching, which are like those of servant leadership (Table 1 also illustrates how the project tasks align with the servant teaching framework). First, emotional healing involves not only expressing care and concerns for students, but also serving as a support system during times of need. To capture this component, the project asks graduate students to identify the current needs and concerns of their selected underrepresented student population. These concerns may be identified from the literature, and from the personal accounts of students in their schools. Addressing these concerns are important to not only facilitate empathy in preservice educators, but also as a way to assist in completing tasks related to empowering students, or confirming students individual assets and using these assets toward success. For the project, the graduate students can be asked to identify the strengths of their chosen population, using literature, personal accounts, or observations. Next, graduate students completing this project will be asked to explain how to implement conceptual skills, or outlining methods that their fictional faculty and staff can use to ensure they are being culturally responsive for the chosen underrepresented population. Specifically, this component of the servant teaching collaboration project asks the graduate students to identify ways that educators can individualize teaching methods to address the needs and concerns of the selected population.

To emphasize servant teaching, the project includes tasks that align with the key dimensions of servant teaching, which are like those of servant leadership (Table 1 also illustrates how the project tasks align with the servant teaching framework). First, emotional healing involves not only expressing care and concerns for students, but also serving as a support system during times of need. To capture this component, the project asks graduate students to identify the current needs and concerns of their selected underrepresented student population. These concerns may be identified from the literature, and from the personal accounts of students in their schools. Addressing these concerns are important to not only facilitate empathy in preservice educators, but also as a way to assist in completing tasks related to empowering students, or confirming students individual assets and using these assets toward success. For the project, the graduate students can be asked to identify the strengths of their chosen population, using literature, personal accounts, or observations. Next, graduate students completing this project will be asked to explain how to implement conceptual skills, or outlining methods that their fictional faculty and staff can use to ensure they are being culturally responsive for the chosen underrepresented population. Specifically, this component of the servant teaching collaboration project asks the graduate students to identify ways that educators can individualize teaching methods to address the needs and concerns of the selected population.

Designing an intervention based upon servant teaching principles involves more than just the support of personnel within the school, but also includes finding resources within the community. Thus, creating value for the community requires the graduate students to find community resources and partners that may assist with the academic and personal growth of the underrepresented student population; additionally, this component of the task outlines how other members of the student body can support this group. As servant teaching is reiterates empowering students, it is also important to provide opportunities for the underrepresented group to engage in leadership tasks. Thus, helping students grow and succeed identifies ways that faculty and staff can recruit students from the chosen population to be more visible and vocal in the school. Specifically, how can the selected group use their strengths in positive ways to lead school and extracurricular activities?

Finally, as the collaboration project is described as professional development training, it is important to highlight ways that the fictional faculty and staff can maintain a professional approach to this topic. The servant teaching factor, put students first, asks the graduate students to find additional resources regarding the underrepresented student population. If faculty and staff wanted to receive ancillary knowledge on the population, and training on how to best serve these students, the graduate students will compile a list of resources for continued professional development. As engaging in culturally responsive practices also requires engaging in fair practices, behaving ethically asks the teaching and school counseling graduate students to review the codes of ethics for both fields to ensure the recommendations included in the professional development PowerPoint are aligned to these standards. Overall, the proposed collaboration project prepares graduate students to work with professionals from different fields within the school, while also taking part in activities to best meet the needs of the diverse populations within their potential schools.

Future Directions and Conclusion

The potential of this collaborative project does not just end within the graduate classroom. As both teaching and school counseling students engage in informal needs assessments and review relevant literature to complete the project, the information they collect can be actually shared with faculty and/or sites at their respective sites. This PowerPoint can serve as a resource for school personnel to address the concerns of an existing student population. As the teaching and school counseling students have received practical experience in collaborating and serve underrepresented student populations, the self-efficacy to engage in similar tasks at future schools of employment has likely increased. Future studies collecting quantitative and qualitative data regarding the impact of school counselor-teacher collaborative partnerships on students’ academic success could validate the proposed model. Though a relatively new concept in education, servant leadership can provide a foundation for educators to approach culturally responsive collaboration.

References

Bond, N. (2011). Preparing preservice teachers to become teacher leaders. The Educational

Forum, 75(4), 280-297.

Carrol, S. A. (2017). Perspectives of 21st century Black women English teachers on impacting

Black student achievement. Journal of Negro Education, 86(2), 115-137. doi:10.7709/jnegroeducation.86.2.0115

Combs, D. & White, R. (2000). There’s madness in these methods: Teaching secondary

methods students to develop interdisciplinary units. The Clearing House, 73(5), 282-286.

Crippen, C. (2010). Serve, teach, and lead: It’s all about relationships. InSight: A Journal of

Scholarly Teaching, 5, 27-36.

Fazzio-Griffith, L., & Curry, J. R. (2008). Professional school counselors as process observers in

the classroom: Collaboration with classroom teachers. Journal of School Counseling,

6(20), 1-15.

Fields, J. W., Thompson, K. C., & Hawkins, J. R. (2015). Servant leadership: Teaching the

helping professional. Journal of Leadership Education, 14(4), 92-105. doi:

1012806/V14/I4/R2

Fitzgerald, R. J. (2015). Becoming Leo: Servant leadership as a pedagogical philosophy. Critical

Questions in Education, 135(1), 75-85.

Hays, J. (2008). Teacher as servant applications of Greenleaf’s servant leadership in higher

education. Journal Of Global Business Issues, 2(1), 113-134.

Henfield, M. S., & McGee, E. O. (2012). Intentional teacher-school counselor collaboration:

Utilizing culturally relevant frameworks to engage Black males. Interdisciplinary Journal

of Teaching and Learning, 2(1), 34-48.

Jacobs, H. H. (1989). Interdisciplinary curriculum: Design and implementation. Association for

Supervision and Curriculum Development. Alexandria, VA.

Jones, C. (2010). Interdisciplinary approach: Advantages, disadvantages, and the future benefits

of interdisciplinary studies. ESSAI, 7, 76-81.

Leeper, L. & Tonneson, V. C., & Williams, R. E. (2010). Preservice elementary education

graduate students’ perception of teacher leadership. International Journal of Teacher Leadership, 3(3), 16-30.

Marbley, A. F., Bonner II, F. A., McKisick, S., Henfield, M. S., & Watts, L. M. (2007).

Interfacing culture specific pedagogy with counseling: A proposed diversity training

model for preparing preservice teachers for diverse learners. Multicultural

Education, 14(3), 8-16.

Marlow, L., Bloss, K., & Bloss, D. (2000). Promoting social and emotional competency through

teacher/counselor collaboration. Education, 120(4), 668-674.

Martinello, M. L., & Cook, G. E. (1992). Interweaving the threads of learning: Interdisciplinary

curriculum and teaching. Curriculum Report, 21(3), 1-6.

Milman, J. (2010). Writing and dialogue for cultural understanding: Multicultural art education

in an art teacher certification program. Art Education, 63(3), 20-24.

National Institutes of Health. (2006). NIH roadmap for medical research. Retrieved from

https://commonfund.nih.gov/sites/default/files/ADecadeofDiscoveryNIHRoadmapCF.pdf

National Science Foundation. (2011). Empowering the nation through discovery and

innovation—NSF strategic plan for fiscal years (FY) 2011–2016. Retrieved from https://www.nsf.gov/news/strategicplan/nsfstrategicplan_2011_2016.pdf

Nieto, S. M. (2003). What keeps teachers going? Educational Leadership, 60(8), 14-18.

Noland, A., & Richards, K. (2015). Servant teaching: An exploration of teacher servant

leadership on student outcomes. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning,

15(6), 16-38. doi: 10.14434/josotl.v15i6.13928

Noddings, N. (2005). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education

(2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press.

Reidel, M., & Draper, C. (2013). Preparing middle grades educators to teach about world

cultures: An interdisciplinary approach. The Social Studies, 104(3) 115-122. doi:

10.1080/00377996.2012.698325

Shoffner, M., & Wachter Morris, C. (2010). Preparing preservice English teachers and school

counselor interns for future collaboration. Teaching Education, 21(2), 185-197. doi: 10.1080/10476210903183894

Sink, C. A. (2002). In search of the profession’s finest hour: a critique of four views of 21st

century school counseling. Professional School Counseling, 5(3), 156-163.

Spears, L. C. (2010). Character and servant leadership: Ten characteristics of effective, caring

leaders. The Journal of Virtues & Leadership, 1, 25-30.

Stringer, S.J., Reynolds, G. P., & Simpson, F. M. (2003). Collaboration between classroom

teachers and a school counselor through literature circles: Building self-esteem. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 30(1), 69-76.

Tate, T. F. (2003). Servant leadership for schools and youth programs. Reclaiming Children and

Youth, 12(1), 33-39.

vanZee, E. H., Jansen, H., Winograd, K., Crowl, M., & Devitt, A. (2013). Fostering scientific

thinking by prospective teachers in a course that integrates physics and literacy learning. Journal of College Science Teaching, 42(5), 29-35.

Webb, D., Webb, T. T., & Fults-McMurtery, R. (2011). Physical educators and school

counselors collaborating to foster successful inclusion of students with disabilities. Physical Educator, 68, 124-129.

York-Barr, J. & Duke, K. (2004). What do we know about teacher leadership? Findings from

two decades of scholarship. Review of Educational Research, 74(3), 225-316.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.