Effects Of Parenting Styles And Parental Involvement On A Student’s Academic Self-Concept In Relation To Their Academic Performance In The 2020 Sea Examination

Kishon J. John

Degree of Master of Arts in Educational Psychology, The University of the Southern Caribbean,

Trinidad and Tobago.

kishonjohn1214@gmail.com

Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationships between three parenting styles, academic self-concept, and academic performance as well as the mediating effect of two of Joyce Epstein’s parental involvement typology (learning at home and volunteering). The quantitative, online cross-sectional survey study utilized a correlational research design was conducted on 75 students and their parents (N=75) selected via purposive sampling from three primary schools in the Port of Spain and Environs Education District. Parents’ and students’ responses were matched and scored for analytical purposes. The correlation between parenting styles and academic performance was computed through Spearman’s Rank correlation coefficient. The results of the study showed that there was a very weak statistically significant association between authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles and academic performance. Permissive parenting accounted for a very weak negative statistically significant association. Spearman’s Rank correlation coefficient was also used to determine the association between parenting styles and academic self-concept. The results showed a very weak statistically significant association between authoritative and permissive parenting and academic self-concept. Contrasting results were present for authoritarian parenting which revealed a low positive statistically significant association. Results from the mediating hypothesis revealed parental involvement insignificantly affected student’s performances. One recommendation for this study focused on the proposal of a longitudinal approach which may provide a comprehensive timeline of how the influence of parenting styles and involvement evolves over time. This study only provided a snippet of early adolescent relations with their parents.

Keywords: parenting style, academic self-concept, parental involvement

Introduction

The current educational climate in Trinidad has led to an emphasis on academic accountability. The Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago has acknowledged that education is the driving force that ensures the development and transformation of a society (Ministry of Education, 2020). The educational system in Trinidad and Tobago comprises of Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE), Primary, Secondary, Technical/Vocational and Tertiary schooling. The primary school level consists of students ages 5-14 where students are promoted from Standard One (Grade 1) to Standard Five (Grade 5). A national level examination is administered at the Standard Five level, the title of this examination is the Secondary Entrance Assessment (SEA). The SEA is used as a benchmark to evaluate a student’s academic capability and judge their overall potential, it’s also used to select student’s admission into secondary schools. The examination is administered to children between the ages 11-14 and consists of three subject areas Mathematics, Language Arts, and Creative Writing.

In spite of, the Ministry of Education’s dedication of establishing and fostering a strong human resource capital for Trinidad and Tobago and ushering students to become 21st century learners, poor academic performances in the Port of Spain and Environs Education District in the Secondary Entrance Assessment (SEA) over the years has become a matter of concern (De Silva, 2021). According to the MOE, there are 90 primary schools within the Port of Spain (POS) and Environs Educational District. Furthermore, based on results from the SEA, this district has consistently ranked within the last four performing districts for the period 2010-2019 when compared to other Districts (Joint Select Committee on Human Rights, Equality and Diversity, 2021). Poor performances have been attributed to: (a) absenteeism, (b) drug use, (c) violence in schools, and (d) community and parent mediocrity (Joint Select Committee on Human Rights, Equality and Diversity, 2020). Notwithstanding, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students led to a high incidence of mental health, which accounted for low levels of self-esteem/motivation, stress, test anxiety, self-efficacy, mental distress, and depression which should be taken into account with student performances (Brooks et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the closure of educational institutions on March 16th of 2020, its impact was both direct and indirect. Direct impact resulted in the disruption to children’s education whereas indirect impact resulted from the significant period of time that children spent at home. The United Nations estimates that 87% of the world’s student population (over 1.5 billion learners) were affected by school closures related to COVID-19 (UNSDSN, 2020). The closure of schools also affected the cancellation or postponement of promotion and final examinations in primary and secondary schools, most notably the SEA examination. Beyond students, parents were also affected in adverse ways. Parents had to adjust, while balancing the demands of work and their domestic life while being confined to their homes, remote working, unstable financial arrangements as well as assuming responsibility for educating their children (Witt et al., 2020). Additionally, they had to support their family and child with limited help from formal and informal social networks and providers (Crawley et al., 2020). These circumstances have placed increased stress on parents. (Cameron et al., 2020; Waite et al., 2021).

Several researchers have attempted to examine features of the familial environment that impact academic achievement in adolescents (Dornbusch et al., 1987; Osuolale, Ogunsola & Ojo, 2014). Some of these family-related factors associated with school performance are parenting styles (Dornbusch et al., 1987; Steinberg, Elmen, & Mounts, 1989; Weiss & Schwarz, 1996) and parental involvement. Parenting styles refer to the child-rearing patterns that characterize parent-child interactions. Within these styles, two dimensions, parental acceptance-involvement and strictness-supervision, are combined to create Baumrind’s (1967) three parenting styles: (a) authoritative, (b)authoritarian, (c) permissive. Maccoby and Martin (1983) added to the theory of Baumrind by including a fourth conceptual style, neglectful. Several researchers followed with concurrent research agreeing that authoritative parenting positively correlated with adolescent academic achievement largely because of the effects of authoritativeness on the healthy development of their self-efficacy (Dornbusch et al., 1987; Steinberg et al., 1989).

Early studies through the 1930’s to 1960’s of Baumrind parenting style typology, employed a variety of theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches, using various factor analytic methods and data from primarily European American, middle-class samples (Power, 2013). Although it is tempting to conclude from the consistency of findings across developing economies, we are some distance from understanding issues tied to parenting and childhood development in the Caribbean region. Existing literature have consistently described Caribbean parents as harsh and demanding in their parenting style, with austere expectation that the child display a level of obedience, manners, respect, as well educational and social proficiency (Leo-Rhynie, 1997; Leo-Rhynie & Brown, 2013).

Most attempts by researchers to systematically examine the parenting practices in English-speaking Caribbean islands have either alluded to the behavioural expectations of children (Wilson, Wilson & Berkeley-Caines, 2003) or measures of harsh physical punishment (Brown & Johnson, 2008; Smith, Springer, & Barrett, 2011). However, a handful of studies have explored parenting styles in English-speaking Caribbean societies. From such an infinitesimal group of studies, it is difficult to ascertain associations between parental warmth and control and social and cognitive skills during the early childhood years in Caribbean societies.

Existing literature have consistently described Caribbean parents as harsh and demanding in their parenting style, with austere expectation that the child display a level of obedience, manners, respect, as well educational and social proficiency (Leo-Rhynie, 1997; Leo-Rhynie & Brown, 2013). Most attempts by researchers to systematically examine the parenting practices in English-speaking Caribbean islands have either alluded to the behavioural expectations of children (Wilson, Wilson & Berkeley-Caines, 2003) or measures of harsh physical punishment (Brown & Johnson, 2008; Smith, Springer, & Barrett, 2011). However, a handful of studies have explored parenting styles in English-speaking Caribbean societies.

Although existing literature indicates parenting styles as a significant factor that influences the academic performances of a student, consideration must be made that it’s not the only factor. Shavelson, Hubner and Stanton (1976) posited that self-concept and academic self-concept can also influence a child’s academic achievement. Several research studies found a direct link between academic self-concept and academic achievement (e.g., Calsyn & Kenny, 1977; Liu, Risser & Kaplan, 1992).

Maser (2007) study reported that a good indicator to measure a student’s academic achievement is by examining their academic self-concept. In his study, students who exhibited high academic self-concept performed significantly greater to those who exhibited low academic self-concept. Another study by Dramanu and Balarabe (2013) investigated the relationship between academic self-concept and academic performance. Findings reveal a statistically significant relationship between academic self-concept and academic performance (r = .306, df = 1468). Parents who are actively involved in their child’s education process increase the educational effectiveness of the time spent together (Becker et al., 1997).

Purpose of the Study

The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationships between three parenting styles, academic self-concept, and academic performance as well as the mediating effect of two of Joyce Epstein’s parental involvement typology (learning at home and volunteering). The goal was that, through results of this study it may (a) assist researchers, educators and policy makers, develop an understanding of key factors that can affect the academic performance of students, (b) influence further research in the study of parenting, (c) develop constructive discourse within the field of education, and (d) assist the Ministry of Education stakeholders in making future recommendations and decisions. There is a possibility that the findings from this study can provide stakeholders with an understanding of possible relationships between parental influences and gender gap performances in the SEA examination.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationships between three parenting styles, academic self-concept, and academic performance as well as the mediating effect of two of Joyce Epstein’s parental involvement typology (learning at home and volunteering). Researchers such as Steinberg et. al (1992) studied the relationship between parenting style and academic performances and Shavelson, Hubner and Stanton (1967) on academic self-concept and academic performances.

Research Questions

- How do parenting styles (authoritative, permissive, and authoritarian) affect the academic performance of students taking the SEA Examination?

- To what extent do parenting styles affect the academic self-concept of students taking the SEA examination?

- How is parental involvement essential in explaining academic performance?

- How does authoritative parenting style, school participation and learning at home explain academic self-concept?

- How does authoritative parenting style, volunteering and learning at home explain academic performances?

Hypothesis

H1: There is a relation between parenting style and academic performance.

H0: There is no relation between parenting style and academic performance.

H1: There is a relation between parenting style and academic self-concept.

H0: There is no relation between parenting style and academic self-concept.

H1: There is a difference with respect to the two dimensions of parental involvement (learning at home and volunteering) and academic performance.

H0: There is no difference with respect to the two dimensions of parental involvement (learning at home and volunteering) and academic performance.

Literature Review

A child’s development is predicated on the role of their parents. Baumrind (1966) viewed the parenting role as a key element where parents have the ability to enable a child to consort and conform to norms while maintaining one’s morals. Baumrind coined the term parenting style in the 1960’s. Rather than studying the relationship of multiple dimensions independently Baumrind concurrently examined parental practices on various dimensions, categorizing parents into various parenting styles. Baumrind proposed a parenting style theory where the belief systems and values that guide parenting roles, the nature of the parent-child relationship and the practices used to achieve a preferred outcome (Kuppens & Ceulemans, 2019).

Building on Baumrind typology, Maccoby and Martin (1983) two- dimensional framework integrated the classification of families according to their levels of parental demandingness (supervision, control, demands for maturity) and responsiveness (warmth, acceptance, involvement). The restructuring of Baumrind’s initial theory produced a fourfold typology. Maccoby and Martin (1983) typology differed from Baumrind’s (1971) model by modifying between two types of permissive parenting, indulgent and neglectful. Initially the term parenting styles was instituted by researchers to investigate family socialization practices during childhood.

Maccoby (1992) authoritative parents practice active listening, listen to the views of their children, allow children to participate in decisions made within the family and also encourage independence and autonomy in the physical and social world. Previous research on authoritative parenting by Baumrind (1991b) showed that parents who practiced this form of parenting were more successful in deterring their children from drug use. Similarly, a study by Williams et al. (2009) deduced that authoritative parenting was significantly correlated to a child’s ability to positively deal with conflict and avert internalizing behaviour. According to Abar and Winsler (2006) During the adolescent period, authoritative parents remain apparent and are beneficial to both adolescence and children. Authoritative parenting is generally linked to positive outcomes for children. Adolescents who are raised in authoritative households tend to cooperate effectively with their peers, develop high esteem, display empathy towards others, attain higher academic achievement (Lamborn, et al., 1991), and attain academic success at elementary school (Steinberg et al., 1994).

Mihret, Dilgasa, and Mamo (2019) study reported that authoritative parenting style was the strongest indicator for students’ academic achievement motivation and was the most widely used form of parenting. Parents who are classified as engaging in a permissive parenting style are characterized as displaying high levels of responsiveness and low levels of demandingness (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Their methods of parenting are unconventional with extensive leniency practiced. Sarwar (2016) study reported that there is a likelihood for permissive parents to protect children from unfavourable consequences. Negative moral development is found to be linked with this form of parenting (Hoeve et al., 2009).

Parents who are classified as engaging in an authoritarian style of parenting are parents that are highly demanding and tend to prioritize obedience and respect for authority. These parents have clear and fixed rules which are outlined to limit the freedom of the child. Studies have shown that authoritarian parenting has negative effects on both adolescents and children, resulting in low self-esteem, low academic achievement, susceptibility to drug use, increased social anxiety (Baumrind, 1991a). Rena, Abedalaziz and Hai Leng (2013) study found that children raised in authoritarian households viewed themselves as unsuccessful for independent learning. Another study conducted by Rauf and Ahmed (2017) on the predictive relationship between authoritarian parenting style and academic performance in 100 school students in Pakistan with the mean age of students 14.62 years. Key findings revealed authoritarian parenting style accounted for 38% variance score of academic performance. Furthermore, authoritarian parenting style negatively impacted academic performances.

Similarly, neglectful parenting involves low levels of responsiveness and demandingness. Maccoby and Martin (1983) believes this is the most deleterious of the four parenting styles as it relates to children and adolescents. Neglectful parents are uninvolved, unresponsive and rejecting. In particular, children raised by neglectful parents develop various negative developmental outcomes such as low self-esteem, depressive symptoms and mood disorders and avoid closeness with peers (Palaez et al., 2008). Evidence from Hoeve et al (2009) indicate that adolescents of neglectful parents tend to engage themselves in externalizing behaviours such as rape, vandalism and petty theft. Other research findings indicate that adolescents who deem their parents as neglectful used significantly more drugs than those who judge themselves from authoritative households (Adalbjarnardottir & Hafsteinsson, 2001).

The literature also highlighted Epstein et al., (2009) theory of parental involvement. Initially Epstein (1987, 1992 & 1993) conceptualized a typology that accounted for different levels of parental involvement in their children’s education. According to Fantuzzo, Mc Wayne, Perry & Childs (2004, as cited in Han, O’Connor, Mc Cormick & Mc Clowry, 2017) research findings on at-home involvement have indicated its significance in contributing to a child willingness to learn, receptive lexicon and positive classroom ethics. Similarly, a study by Mora and Escardíbul (2018) findings showed the better the adolescent’s perception of the home environment, the greater is the involvement of his or her parents in the provision of homework support. A child’s positive perception of the home environment increased the probability of parental involvement with the adolescent’s homework by around 0.068 units.

Multiple researchers have been able to provide empirical evidence to provide a positive and direct relationship between parental involvement and a student academic achievement. Mante, Awereh and Kumea (2014) indicated that when parents are significantly involved in their children’s learning it has a positive effect on their school performances. Overall, the meta- analysis demonstrated a positive relation between general parental involvement and achievement in middle school. Other studies concluded similar results affirming the positive association of parental involvement with academic achievement (Fan & Chen, 2001; Jeynes, 2003; Steinberg et al., 1994).

According to Marsh and Martin (2011) self-concept is a multifaceted construct, where one of its facets involves academic self-concept. Academic self-concept and students’ performance are related. Dramanu and Balarabe (2013) study of 756 male and 714 female students investigated the relationship between academic self-concept and academic performance. Findings reveal a statistically significant relationship between academic self-concept and academic performance (r = .306, df = 1468). Hanan, Kabeer and Nady (2016) study of 182 primary and preparatory school age children 9-15 years old to study the relationship between academic self-concept and students’ performance among school age children. Findings revealed the correlation between academic self-concept and students’ academic performance. Pearson correlation statistic is .256 which is descriptively interpreted as having “low correlations” and supported by a significant p-value of.045 respectively. It implies that the students’ self-concept was positively related to their academic achievement.

Research Design

This quantitative, online cross-sectional survey study utilized a correlational research design. According to Lavrakas (2008), the cross-sectional survey is often described as a snapshot of the population from which data is being gathered. This is because the research design collects data to make inferences about the population of interest at one particular point in time. Since the researcher’s aim was to gather data concerning the students who wrote the 2020 SEA examinations at a single point in time, without any repeated measures of the sample subjects, the cross-sectional survey was best suited and chosen for the research objective. A correlational research design was implemented.

Participants and Data Collection Procedure

For this study, the students who took the 2020 Secondary Entrance Assessment (SEA) and their parents were selected as the population of interests. Due to the nature of the material being studied, only students ages 10-14 years (75) and their parents (75) were studied. A sample of 150 participants was collected. Parents’ and students’ responses were matched and scored for analytical purposes. A purposive sampling method was used to source students ages 10-14 who completed the 2020 SEA Examination from three (3) schools across the Port of Spain and Environs Education District.

Results

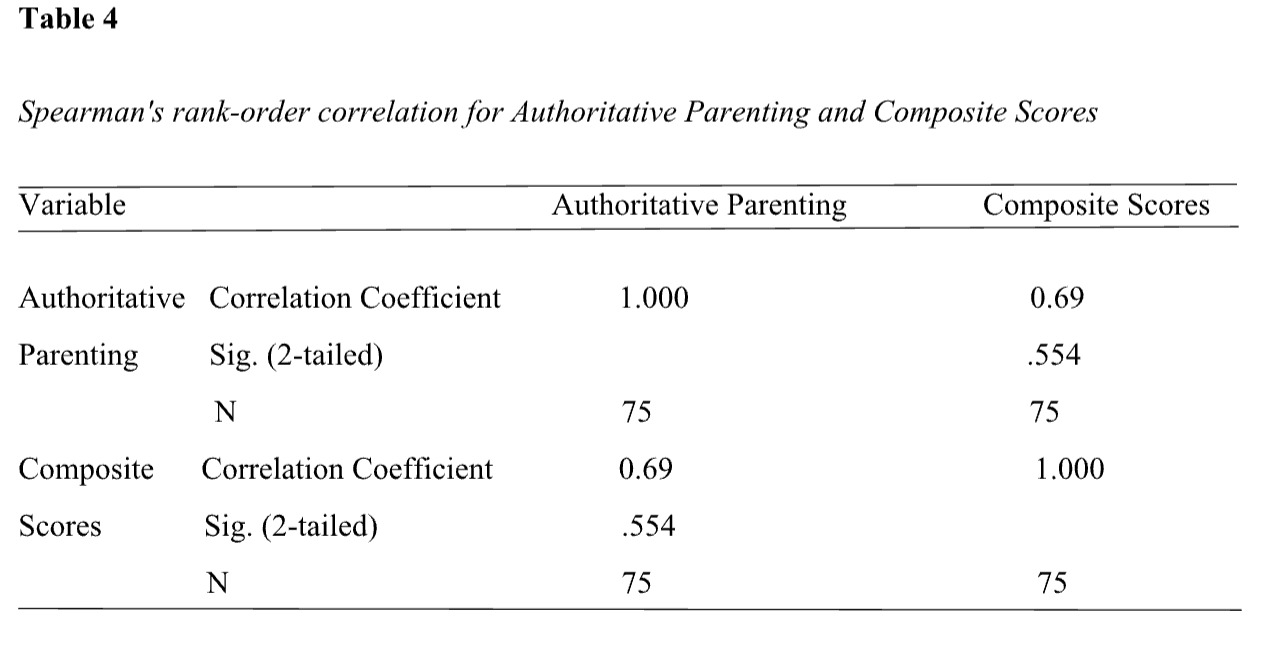

Table 4

Spearman’s rank-order correlation for Authoritative Parenting and Composite Scores

Findings for the Spearman’s rank-order correlation, in Table 4. indicated that there was a

very weak statistically significant relation between variables (rs [75] = .069, p = .554).

Regarding the p-value =.554 the null hypothesis is totally accepted, which indicates that there

was enough evidence to state that the correlation does not exist in the population.

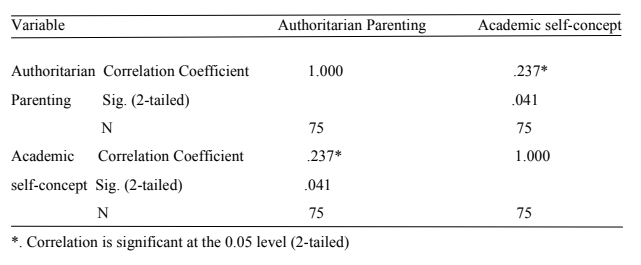

Table 9

Spearman’s rank-order correlation for Authoritarian Parenting and Academic self-concept

Findings from the Spearman rank-order correlation as shown in Table 9. indicated that

there was a low positive statically significant relation between parental control and academic

self-concept (rs [75] = .237*, p = .041, that there was enough evidence to state that the

correlation does exist in the population.

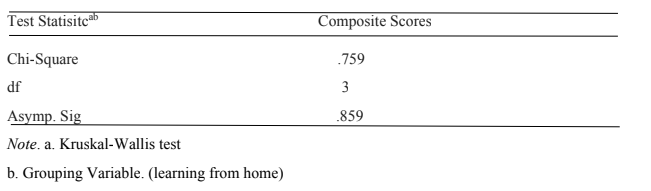

Table 13

Kruskal-Wallis test for mean difference

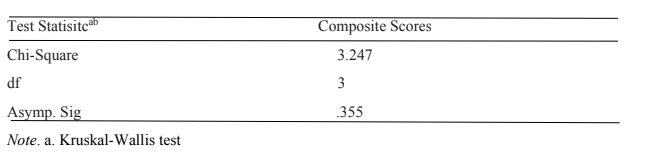

Table 14

Kruskal-Wallis test for mean difference

b. Grouping Variable. (volunteering)

The results in Table 13. As determined by the Kruskal-Wallis H test, parental involvement (learning at home) insignificantly affected student’s performances H (3) = .759, p = .859. Regarding the p-value =.859 the null hypothesis is totally accepted. Table 14. results 59 59 determined by the Kruskal-Wallis H test, also showed parental involvement (volunteering) insignificantly affected student’s performances H (3) = 3.247, p = .355). Regarding the p value=.355 the null hypothesis is totally accepted.

Discussion

The present study sought to identify relationships between parenting styles and academic performances of the early adolescent population completing the 2020 S.E.A. Examination. With very weak statistically significant associations being identified, it begs the question of whether the documented effects of parenting styles on children and adolescents exist within the middle adolescent sample. The findings of the current study were incongruous with previous research. This finding wasn’t congruent with previous studies suggesting that authoritative parenting had a strong correlation with academic performances (Dornbusch et al., 1987; Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1989; Steinberg et al., 1991). One possible explanation for the weak association between parenting styles in this study and academic performances could be the parenting styles used by Caribbean parents.

According to Leo-Rhynie (1997) and Leo-Rhynie & Brown (2013) Caribbean parents are harsh and demanding in their parenting style, with austere expectation that the child displays a level of obedience, manners, respect, as well educational and social proficiency. Studies have shown that authoritarian parenting has negative effects on both adolescents and children, resulting in low self-esteem, low academic achievement, susceptibility to drug use, increased social anxiety (Baumrind, 1991a).

A second explanation for the findings could be explained within the parameters of the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 for parents became even more paramount as children were restricted from outdoor activities, limiting contact with peers and family members, and deprived of their personal development (Fegert, Vitiello, Plener & Clemens, 2020). Parents have been equally affected balancing the demands of work and their domestic life while being confined to their homes, remote working, unstable financial arrangements as well as assuming responsibility for educating their children (Witt et al., 2020). Additionally, they had to support their family and child with limited help from formal and informal social networks and providers (Crawley et al., 2020).

Prior research has estimated that parental involvement as a global construct and found that involvement does serve as a mediator of parenting styles on academic performance. Parental involvement, when broken into two components, does not exert as strong of an effect on the relationship between parenting styles and academic performance. The results showed no relation to academic performances which may be attributed to remote learning. During the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries introduced restrictions on the functioning of schools and moved the educational process to virtual networks and family homes (Song et al., 2020).

The present study sought to identify relationships between parenting styles and academic performances of the early adolescent population completing the 2020 S.E.A. Examination. With very weak statistically significant associations being identified, it begs the question of whether the documented effects of parenting styles on children and adolescents exist within the middle adolescent sample. The findings of the current study were incongruous with previous research. This finding wasn’t congruent with previous studies suggesting that authoritative parenting had a strong correlation with academic performances (Dornbusch et al., 1987; Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1989; Steinberg et al., 1991). One possible explanation for the weak association between parenting styles in this study and academic performances could be the parenting styles used by Caribbean parents.

According to Leo-Rhynie (1997) and Leo-Rhynie & Brown (2013) Caribbean parents are harsh and demanding in their parenting style, with austere expectation that the child displays a level of obedience, manners, respect, as well educational and social proficiency. Studies have shown that authoritarian parenting has negative effects on both adolescents and children, resulting in low self-esteem, low academic achievement, susceptibility to drug use, increased social anxiety (Baumrind, 1991a).

A second explanation for the findings could be explained within the parameters of the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 for parents became even more paramount as children were restricted from outdoor activities, limiting contact with peers and family members, and deprived of their personal development (Fegert, Vitiello, Plener & Clemens, 2020). Parents have been equally affected balancing the demands of work and their domestic life while being confined to their homes, remote working, unstable financial arrangements as well as assuming responsibility for educating their children (Witt et al., 2020). Additionally, they had to support their family and child with limited help from formal and informal social networks and providers (Crawley et al., 2020).

Prior research has estimated that parental involvement as a global construct and found that involvement does serve as a mediator of parenting styles on academic performance. Parental involvement, when broken into two components, does not exert as strong of an effect on the relationship between parenting styles and academic performance. The results showed no relation to academic performances which may be attributed to remote learning. During the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries introduced restrictions on the functioning of schools and moved the educational process to virtual networks and family homes (Song et al., 2020).

Remote learning is an approach to learning which takes education outside the school premises and does not require physical presence of teacher or student alike (Moore, 2019). According to (Bell et al., 2017) E-learning seems to be easier and more accessible than traditional learning due to its flexibility, however there are barriers. A study conducted by (Sheridan et al., 2012) have shown that parental involvement in learning at home been associated with cognitive success but also with the development of social competences which has a positive relation to academic performance.

Limitations of this Study

This study sought to produce findings that were consistent with current literature where authoritative parenting style had a strong positive relation to academic performances and academic self-concept. It was also expected that academic performances were mediated by parental involvement. One of the major limitations of the present study is the time lapse between completion of the 2020 S.E.A. Examination and the self-report measures. This study relied solely on adolescent’s reports of their parents and parent’s perspective of their forms of parenting and level of parental involvement in 2020. This significant time lapse may have significantly impacted the results of this study. Closure of schools due to the COVID-19 pandemic is another limitation of this study, parental attitudes, level of involvement, mental health problems, loss of jobs, loss of loved ones, and increased responsibility of working from home and supporting their children at home will have been significantly affected due to such.

One limitation of this study was the relatively small sample size used. Participants were contacted via telephone, SMS and email were very few responded and showed willingness to participate. Another limitation of this study is the omission of socioeconomic status of participants or their educational district. Over the last 50 years, much has been added to the research literature on this topic. It has become ubiquitous in research studies that the student’s socioeconomic background, and that of the school they attend, as contextual variables when seeking to explore potential influences on academic performances (Thomson, 2018). Morgan, Farkas, Hillemeier. and Maczuga (2009) findings of children who reside in low-SES households and communities reveal that they develop at a slower pace academically than those from higher SES. Low SES in childhood is associated to poor cognitive development, language, memory, socioemotional processing, and consequently poor income and health in adulthood (Buckingham, Wheldall, & Beaman-Wheldall, 2013).

Aikens and Barbarin (2008) postulated that educational institutions in low-SES communities are frequently under-resourced, which can negatively impact their academic development and outcomes. Lastly, the relatively small sample size from each school did have significant implications to the analysis and findings. Future researchers could collect data from both parent and child in order to evaluate the relationships void of the pandemic in Trinidad and Tobago.

Recommendations

The vast majority of participants from the study reside in two-parent households. Many children are raised in single parents or have parents splitting their time between two residences, it is paramount to assess the roles that these parents play and their level of involvement. In addition, this research excluded siblings who may have written the exams together, future research could study siblings who are raised in the same household and completed examinations at the same time. This would allow the researcher to evaluate how the parent’s style influences each child within the family to determine if parenting styles exert as strong an effect as previously postulated or if other influences are more important to the child’s development. Equivalently, a longitudinal study can provide a comprehensive timeline of how the influence of parenting styles and involvement evolves over time. This study only provided a snippet of early adolescent relations with their parents. Having longitudinal data would allow the researcher to compare the effect of parenting styles in childhood, when it is reported to have a stronger influence, to the effect parenting styles have through adolescence.

References

Aikens, N. L., & Barbarin, O. (2008). Socioeconomic differences in reading trajectories: The contribution of family, neighborhood, and school contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.2.235

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative control on child behaviour. Child Development, 37(4), 887-907. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126611

Becker, H. J., Nakagawa, K., & Corwin, R. G. (1997). Parent involvement contracts in California’s charter schools: Strategy for educational improvement or method of exclusion. Teachers College Record, 98(3), 511-536.

Brown, L., & Iyengar, S. (2008). Parenting styles: The impact on student achievement. Marriage & Family Review, 43(1), 14-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494920802010140

Buckingham, J., Wheldall, K., & Beaman-Wheldall, R. (2013). Why poor children are more likely to become poor readers: The school years. Australian Journal of Education, 57, 190-213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944113495500

Calsyn, R. J., & Kenny, D. A. (1977). Self-concept of ability and perceived evaluation of others: Cause or effect of academic achievement? Journal of Educational Psychology, 69(2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.69.2.136

Crawley, E., Loades, M., Feder, G., Logan, S., Redwood, S., & Macleod, J. (2020). Wider collateral damage to children in the UK because of the social distancing measures designed to reduce the impact of COVID-19 in adults. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 4(1), e000701. https://doi.org/10.1136/ bmjpo-2020-000701

De Silva, R. (2021, January 19). Concordat and SEA not to blame for poor school performances. Trinidad and Tobago Guardian. https://www.guardian.co.tt/

Epstein, J. L. (1987). Parent involvement: What research says to administrators. Education and Urban Society, 19(2), 119-136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124587019002002

Joint Select Committee on Human Rights, Equality and Diversity. (2021, November 24). Inquiry into the Right to Equal Access to Education with specific focus on the Underperformance of Schools in the Port-of Spain and Environs District with respect to Performance in Terminal Examinations. Second Session of the Twelfth Parliament of Trinidad and Tobago. http://www.ttparliament.org/reports/p12-s2-J-20211112-HRED-R1.pdf

Leo-Rhynie, E. (1997). Class, race, and gender issues in child rearing in the Caribbean. In J. L. Roopnarine & J. Brown (Eds.), Caribbean families: Diversity among ethnic groups (pp. 25- 55). Norwood, NJ: Ablex

Leo-Rhynie, E., & Brown, J. (2013). Childrearing practices in the Caribbean in the early childhood years. In C. Logie, J.L. Roopnarine (Eds.), Issues and perspectives in early childhood development and education in Caribbean countries (pp. 30-62). La Romaine, Trinidad: Caribbean Education Publishers.

Liu, X., Kaplan, H. B., & Risser, W. (1992). Decomposing the reciprocal relationships between academic achievement and general self-esteem. Youth & Society, 24(2), 123–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X92024002001

Maccoby, E., & Martin, J. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In E.M. Hetherington (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol 4. Socialization, personality, and social development, 1-101. New York: Wiley

Maser, K. (2007). The level of student participation in extra-curricular activities, adolescence development, and student achievement. (Order No. 3272790) [Doctoral dissertation, Dowling College]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Power T. G. (2013). Parenting dimensions and styles: a brief history and recommendations for future research. Childhood obesity (Print), 9 Suppl(Suppl 1), S14–S21. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2013.0034

Shavelson, R. J., Hubner, J. J., & Stanton, J. C. (1976). Self-Concept: Validation of Construct Interpretations. Review of Educational Research, 46(3), 407-441. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543046003407

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S., Darling, N., Mounts, N., & Dombusch, S. (1994). Over-time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent and neglectful families. Child Development, 65, 754-770. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131416

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.