The Use of School Counselor Lunch Duty to Increase Student Contact

Dr. Jeff Cranmore, Dianna Conkling, and Melissa Howard

jeff.cranmore@my.gcu.edu

Abstract

This study explored a lunch time counseling station in a large suburban Texas high school. The purpose of the station was to give students access to school counselors to ask questions; however, less than one percent of the student body took advantage of this program. The authors noted that the large expense of personnel when compared to the low number of students served made this approach not an effective use of school counselor’s time. While students need access to school counselors, they perceived that counselors were not available, as they were not in their office. Further study is needed to find effective ways to provide counseling services to all students, and to utilize school counselors to their fullest extent.

Keywords: School counselors, guidance curriculum, administrative expectations, and effective use of school counselor time.

The Use of School Counselor Lunch Duty to Increase Student Contact

The purpose of this action research study was to explore the effectiveness of a Counselor’s Corner question and answer station at a large suburban high school in North Texas. School counselors participated in a daily lunch activity, to allow students to ask questions. While access to school counselors is important for student development, clear expectations on how school counselors can deliver a comprehensive guidance program to all students are still needed. Further, counselors are often used in administrative tasks, rather than providing specific counseling duties.

School counselor play a vital role in support students. There remains some confusion on best practices on the part of counselors and school leadership, on how to best provide services to all students. This study sought to address the use of school counselors in a lunch setting. While the addition of more adult supervision may provide some support of discipline issues, it may not provide the most beneficial setting to provide counseling services, as defined by state and national standards to all students.

The study occurred at large high school in north Texas, with over 2700 students, with a demographic makeup being approximately 60% white, 24% Hispanic, and 13% African American. The school has a total of six counselors, with caseloads ranging from 525-600 students each. The six counselors consisted of five female counselors and one male. Four of the counselors had been at the campus for six to ten years. The other counselors were in their first and second years at the campus. All counselors at the campus had been counselors for at least three years, with the highest counseling experience was 19 years. Five of the counselors were Caucasian, and one was African American. Students are assigned a counselor based on their last name. Each counselor was responsible for a certain portion of the alphabet. The Counselor Corner was an administrative decision, with three counselors assigned to each of the five lunches four days a week. Counselors alternated three lunches one week, and two the next week. No clear directives were given on the nature of the counseling support to provide. For this study, the data was collected only by one group of three counselors.

Review of Literature

The Texas Education Agency (TEA) defines the role and responsibilities of school counselors in A Model for Comprehensive, Developmental Guidance and Counseling Program for Texas Public Schools (2004). This guide serves as model to assure requirements for meeting the developmental needs of the entire student population. The model consists of four mandatory foundational components to incorporate in balanced school counselor programs within the schools: guidance, responsive services, individual planning, and system support. According to TEA, high school level school counselors’ time allotment should be 35%-45% guidance curriculum 30%-40% responsive services 5%-10% individual planning 10%-15% system support 0% non-guidance. While these recommendations offer a guide, there is not a legal mandate for districts to follow these time allotments.

Research conducted by The College Board (2013) found that almost 70% of school counselors are assigned clerical and administrative tasks. School counselors reported being pulled out of counseling to be substitute teachers or to perform state testing. Counselors are charged with ensuring “that all students, regardless of their background, have equal access to a high-quality education” (p. 16). However, this can be difficult when counselors are pulled away from students.

There are a variety of tasks and expectations for school counselors. Their specialized skills may include college and career readiness, mental health services, and dealing with any number of situations. Collins (2014) recommended that school counselors should have the time and resources to “provide short-term clinical-based interventions to improve child and adolescent mental health” (p. 415). Alger and Luke (2015) found that counselors perceived that their role included many facets. One counselor noted that they were responsible for “Advisement and social-emotional development, college and career preparation, course scheduling, as well as other options for after high school” (p. 23). DeKruyf, Auger, and Trice-Black (2013) contended that school counselors should be able to ensure the mental health of their students. The authors cite key barriers as excessive student to counselor ratios, administrative perceptions of counselor roles, and a lack of clinical supervisions to assist students in mental health counseling.

Research by Gysbers (2013) found that school counselors served students by providing activities that “support student planning by giving emphasis to the development and use of decision- making, goal-setting, and planning skills” and by stressing “basic academic and career and technical education preparation skills” (p. 287). The two tasks were central to the relationship between school counselors and their students. Further, these skills are essential to students’ future success outside of high school settings.

While this research points to importance of school counseling, it is still unclear how to best meet the needs of all students, or how counselors and administrators may differ in opinion on how to utilize counselor time. Due to inconsistent job duties or responsibilities, school counselors may not be available to effectively advocate for and serve all populations (Slaten, Scalise, Gutten, & Baskin, 2013; Test, 2015; Trevison, 2000). Research found that school counselors are often asked to perform a variety of non-counseling duties, including lunch duty, standardized testing organization, and managing other mandated programs (Howell, Bitner, Henry, Eggett, Bauman, Sawyer, & Bryant, 2007). This study sought to fill in the gap of research addressing the use of school counselors in a lunch duty setting.

Method

The researchers chose an action research approach to explore this phenomenon. Efron and Ravid (2013) noted that unlike other traditional approach to research, action research allows the researchers to improve practices, while being involved in the process. Further, the researchers could draw data from a current event to make recommendations for change. The practical and constructivists nature of the design, allowed researchers to generate new knowledge about the process of engaging students during their lunch by school counselors. The practical nature of the problem encouraged counselors to find ways to increase contact with students, thus serving a greater portion of the student body.

The primary data sources for the study came from observational data and the use of tally sheets, to quantify numeric values of student contacts. As the panel of school counselors noted each student contact, they confirmed on the type of contact, serving as an internal means of validation of the data. Additional data came from the end of the year senior survey, and the students’ perceptions of counselor access and availability. The perceptional data was used in making meaning of the results, and is referred to in the discussion section.

Using a spread sheet, the panel of three school counselors noted student contacts while assigned to a Counselor Corner table at lunch. The three counselors were assigned an alternating pattern of three lunches daily for one week, and two the next week. The Counselor Corner operated at every lunch, four days each week. A second set of three school counselors operated the table on an alternating schedule. No data was collected from the second group. While most days, the complete panel was present, if emergencies occurred, the remaining counselors continued to operate the table and note student interactions.

Data analysis included tabulation of tallies marks, development of themes, and reading and coding of student responses to senior surveys. These various codes and themes were created after each student interaction were marked, and a full consensus was reached by the three counselors on the type of contact (Efron & Ravid, 2013). Upon completion of theme development and analysis, an additional means of validity occurred through a final consent of the findings from the full team of counselors collecting the data. This form of triangulation served to ensure the data was presented clearly and without bias. Themes collected were then compared to the responses of the senior class exit survey regarding counseling services. The survey consisted of open ended response questions regarding the types of counseling services received and any recommendations for increased service. A final piece of data came from student requests to meet with their counselor during the semester.

Results

Data collection occurred over the fall semester of 2015. A total of 40.5 hours of lunch duty was recorded and analyzed. During that time, as students approached the counseling table, the counseling staff addressed any questions, and made notes of the nature of the inquiry. A total of 63 student contacts were made over the semester. The majority of these contacts involved non-counseling questions. These included: Are you selling the football tickets here? Can I buy a spirit shirt here? These contacts were noted, however as they did not relate to any school counseling function, there were not analyzed in the data. Table 1 indicates the specific student contacts.

The remaining 20 student contacts were more in line with components of the Texas Comprehensive Guidance Model of school counseling functions. The location of specific counseling related items included asking where certain forms, such as schedule changes, were located, as well as the location of college events, such as where visiting college representatives could be met on a certain day. While these questions could have been answered by any individual, as they often had to do with college or scheduling, this category was included as a non-specific counseling function. Specific questions regarding schedule changes were identified as a form of individual planning. The one college application question most aligned with the college and career planning component of the Texas Comprehensive Guidance Model, while the students seeking help with personal issues were identified as a form of system support. Figure 1, below, shows a breakdown by the Texas category of each of the types of student questions.

These 20 student contacts resent the opportunity of school counselors to interact with students in their job capacity. While this data was collected over a semester it represented 40.5 hours of collection, by three school counselors. This equates to 121.5 hours of school staff time, to serve 20 students, in a school with a student body of 2715, meaning the counselors served approximately .007 percent of the student population.

Discussion

Several themes developed from the data that may be relevant to interpreting the results. The first had to do with the use of the school counselors. When the administration made the decision to implement the Counselor Corner, there was no input from the school counselors. Further, there was never a clear indication that the counselors were at lunch to answer questions. The school leadership proposed several signs to indicate the purpose of the counselors, however, no signs were created, or messages sent to the student body. This lack of advertising may have had a large impact on the usage of the Counselor Corner program.

This is made even more obvious when referring to the student responses to the end of year senior survey of counseling services. An overwhelming theme that developed was that students perceived their counselor was not available. Comments such as, “My counselor was never in their office” may show that students did not perceive the designated time allotted for counseling questions at lunch was ever made clear to them. It is also important to note the in language of the comment that students sought their counselor in their office. Counselor office data found a number of students requested appointments with their counselor during the time they were assigned to the cafeteria but did not come to meet with them there. They requested to be called back to the office, when the counselors returned. Students may have had some concerns contacting their counselor with confidential or private information in public areas. Campus data reported several mental health issues (100+) during the academic year, including self-harm attempts, anxiety, and depression; however, no reports were filed with the counselors during their assigned lunch periods. Students may have perceived counselors as being on a lunch duty versus being available to work with them during this time. This perception may have served as a barrier to academic or mental health services (DeKruyf, Auger, & Trice-Black, 2013; Gysbers, 2013)

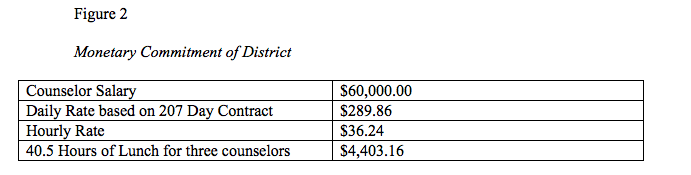

A second area to address in the effectiveness of this program can be related to amount of school resources spent in regards to student contact. The average salary of each of the school counselors was approximately $60,000. Based on their 207-day contract, the hourly rate of school counselors was $36.24. With three counselors spending one to one and a half hours in lunch daily, the expense of resources at a single lunch was 56.36 per lunch. The sample of three counselors in the semester of lunch duty represent a district expense of $4,403.16 for 40.5 hours of lunch duty. Figure 2 shows this.

While the goal was providing information to the student body, less than one percent of the students used this service. Looking at the 20 counseling related questions, the district encumbered resources that equaled approximately 6 work hours per question, at a cost of $220.16 per question. In regards to the nature of the questions and how they directly related to defined counselor roles in the state of Texas, only 12 questions met the definition of duties assigned specifically to counselors. In this case, the cost per question to the district exceeded $366. This monetary summary may be cause enough to consider the expense to return ratio for this type of model of counseling services.

A final theme that emerged from the data was the lack of alignment to the Texas Model of Guidance. One of the stated purposes of the model is to ensure adequate access of counseling services to all students. While the services of counselors were available to the entire student body, less than one percent used this service. Additionally, it should be noted that counselor planned guidance activities related to academic promotion, college readiness, and mental health continued. On days that counselors were classrooms presenting guidance, the Counselors Corner was closed. Further, the stated time for non-counseling duties was 0%. While one may argue that counselors were there to provide access to services, they were also used to reduce the adult to student ratio in lunch times. No activity provided by the counselors could be linked to Guidance, which was named as the state’s expectation where most counselor time should be spent. This aligns with prior research that shows a lack of a clear definition of the role of school counselors by campus administration (The College Board, 2013; Collins, 2014; DeKruyf, Auger, & Trice-Black, 2013).

In looking at the data, it is difficult to find any measure that can be used to show that the innovation provided any success in terms of providing counseling services to students. At the conclusion of the data collection period, the program was discontinued for the remainder of the school year. Many factors were included in this decision, but the primary reason was that high school counselors were pulled from the lunch period to complete the registration process for the following school year. The registration process involves several components related to the Texas Compressive Guidance Model of Counseling, including individual planning and college and career readiness.

Limitations

While looking at the present data, many limitations present themselves. One of the first limitations was the role of the school counselors in this administrative mandate. Counselors were not involved in the planning or implementation. All details, including those of advertising the initiative, were decided by the administrative team. A further limitation of the study comes from the student perception data. While general comments were available from the survey, specific interview questions may have better served to clarify student perceptions and meanings. Interview data might also explore student perceptions of any other barriers, either procedural or cultural that might have limited student access to counseling services. Finally, data was formally collected by only one half of the campus counselors. The full data set may have shed additional insight on the trends in student contact patterns.

Conclusion

Upon reviewing the data, several conclusions can be drawn from this experience. While an attempt was made to provide services to students, this attempt was not clearly communicated to staff, students, or parents. Clear expectations on the part of the school administration may have increased the number of students served by counselors during this time. More importantly, clear and open communication between campus administration and counselors may have resulted in a better defined goal. While not addressed in the data collected, there were several questions as to whether counselors were present to serve students, or to assist in lunch duty. This is an area of future study, to further define the role of school counselors, and how school administrators see the role of counselors. Further, students may have perceived counselors as being busy or on a non-counseling duty when out of their offices. This may have actually served as a deterrent for some students to speak with counselors.

The results do point to possible areas for future study. One area that remains to be clearly defined is the proper use of school counselors, and their role within the school. More clearly defined roles for school counselors may lead to stronger school counseling programs, as it will allow counselors and school leaders the opportunity to collaborate to provide developmentally appropriate counseling services for all students. Further, additional research may address successful strategies for incorporating a fully inclusive guidance model throughout a campus. Approaches that focus on one student at a time often fail to meet the needs of all students. A systematic approach that addresses all students is needed to ensure equal access for all students and families. Finally, research is needed to address the perception of school counselors and their roles with campus administration. While quantitative surveys have been used to address this, more qualitative approaches would allow the voices and lived experiences of both school counselors and administrators to be heard. Additional student perception data would also provide valuable information for school counselors on how to meet their needs.

There is little doubt that students in school systems can benefit from emotional, social, and academic support. These areas are clearly defined goals of school counselors. With the vast array of challenges that students face, especially at a high school level, utilizing school counselors to support all students is essential. There is a moral precedent to ensure that all students have equal access to the supports provided by a comprehensive guidance program. This research sought to address questions of effectiveness of one approach in supporting students. The researchers feel that this model provides little success in reaching all students, at a high cost of resources. It is the hope of the researchers that changes can be made to improve student access to these valuable counseling services at multiple campuses across Texas and the nation.

References

Alger, A. L., & Luke, M. (2015). The School Counselor Perspective: Preparing Students to be College and Career Ready within a Comprehensive School Counseling Program.

Practitioner Scholar: Journal of Counseling & Professional Psychology, 4(1), 17-35.

The College Board. (2013). School counselors underutilized, survey says. District Administration, 49(2), 16.

Collins, T. (2014). Addressing mental health needs in our schools: Supporting the role of school counselors. The Professional School Counselor 4(5), 413-413.

DeKruyf, L., Auger, R. W., & Trice-Black, S. (2013). The role of school counselors in meeting

students’ mental health needs: Examining issues of professional identity. Professional School Counseling, 16(5), 271-282.

Efron, S. E. & Ravid, R. (2013). Action research in education. New York, NY: The Guilford

Press.

Gysbers, N. C. (2013). Career-ready students: A goal of comprehensive school counseling programs. The Career Development Quarterly, 61(3), 283-288. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1431919360?accountid=7113

Howell, S. L., Bitner, K. S., Henry, N., J., Eggett, D. L., Bauman, G. J., Sawyer, O., & Bryant,

- (2007). Professional development and school counselors: A study of Utah school counselor preferences and practices. Journal of School Counseling, 5(2), 42 pp.

Slaten, C. D., Scalise, D. A., Gutten, K., & Baskin, T. W. (2013). Early career school counselors’ training perspectives: Implications for school counselor educators. Journal of School Counseling, 11(20), 1-34.

Test, T. (2015). School counselor preparation to serve intellectually gifted students: a Texas state perspective. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. (AAT 949894794)

Texas Education Agency (TEA; rev. 2004). A model comprehensive, developmental guidance and counseling program for Texas public schools; A guide for program development pre-k-12th grade. Austin, TX: TEA.

Trevisan, M. S. (2000). The status of program evaluation expectations in state school counselor certification requirements. American Journal of Evaluation 21(1), 81-94

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.